Founder of Naramata, Summerland and Peachland.

Naramata is a bit of an odd-sounding name for a village on the south-east edge of Okanagan Lake, isn’t it? In this region most towns are named after a founder, or a First Nations place name, Naramata sounds more like it should be in Japan. Indeed, there exists such a place, although it’s a dam and not a village. Of course, that Japanese dam did not exist when Naramata’s founder, John Moore Robinson — his portrait is on the right — came up with the name. The odds are that he simply liked the name’s romantic sound and simple spelling, and the rest is pure coincidence. Of course, by that point, he had had a fair bit of practice at naming the place.

Until John Moore Robinson came along, Naramata had been called Nine Mile Point, reflecting the fact that the land the village sits on forms a point into the lake and is 9 miles from Penticton. John Moore Robinson acquired the land, some 3500 acres, from the South Okanagan Land Company to develop it for sale into 10-acre fruit tree lots that would appeal to eastern farmers and British settlers. He first renamed it East Summerland, after another town that he had founded and named Summerland, and offered a ferry connection between the two, using the steam yacht Rattlesnake to make the 5 km jaunt across Lake Okanagan.

The name East Summerland, however, was quickly replaced by a new one: Brighton Beach. The likely reason behind this choice is that part of J. M. Robinson’s education took place in New York City, and he visited that city’s Brighton Beach regularly. Evidently he had more than a passing fondness for the name.

(Click for a larger photo.)

A short time later, John Moore Robinson succumbed to a final flight of fancy, and renamed the town Naramata. How J.M. Robinson came up with that name is a subject of some contention. The story that he himself promoted involved a séance — a very fashionable activity at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century. Robinson told the story of hearing the town medium, Mrs. Gillespie, converse with an “Indian Chief”, who spoke of his wife “Narramattah”, whose name was interpreted by the medium as meaning the “smile of Manitou“.

Today, this origin coexists with more convoluted theories involving sunsets over the hills on the west side of the lake. Regardless of the name’s origin, John Moore Robinson finally stayed with it and advertised it broadly to both would-be immigrants from the UK, and to farmers in Manitoba, where he had spent a number of years teaching, running a couple of newspapers and had even been elected to the legislature. His brochures targeted other markets as well, such as potential purchasers in Alberta and even in Ontario, where he was born. J.M. Robinson was well-educated, a natural salesman, and an entrepreneur. By the time he founded Naramata, Robinson controlled much of the village, including the bank, the post office, the Naramata Supply Company, the Naramata Hotel, a bottling plant (he had a penchant for seltzer water), and a variety of other buildings.

Early Settlement

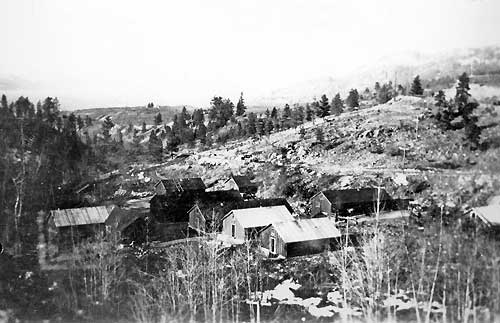

By 1907, a rough wagon road had been pushed through from Penticton to Naramata. And rough it was: simply keeping it passable for the horse-drawn wagons required regular grading, accomplished by men with teams of horses pulling a grader. The more direct route anywhere was still by boat, which would take passengers and freight from the dock in Naramata to the docks of Penticton, Summerland, Peachland or even Okanagan Landing, at the north end of the lake and now part of Vernon.

True to his inspiration, John Moore Robinson settled in Naramata, unlike so many land developers that moved on to other, greener, pastures. By 1907 Naramata had a one-room schoolhouse and by 1908, John Moore Robinson had built the Naramata Hotel (now the Naramata Heritage Inn) and an “Opera House” which was located on the upper floor of his Naramata Supply Company building, mentioned in Penticton’s newspaper at the time as a “handsome building”.

to 1914 when it was replaced by a bigger

building to accommodate the growing community.

From the start Naramata had some interesting features for such a new and small place. John Moore Robinson had a small electrical generating plant built on the creek that produced electricity with a Pelton wheel (a type of turbine). In his own residence, the Naramata Hotel, Robinson piped water through the basement and installed a similar system to provide electricity for lights. A couple of telephones were also in use between the Naramata Hotel and the Naramata Supply Company. It wasn’t until a few years later, however, that an underwater cable was laid between Naramata and Summerland, which allowed for a real connection to the rest of the world.

Soon, regattas were held during the summer, drawing people from around the lake. The first one was held in 1908 and was such a success that the following year three regattas were held. Slightly to the south of the Naramata Hotel, a grandstand, capable of seating up to 800 people, was built for visitors to take in the regattas. Regrettably, it burnt to the ground only a couple of years later. Interestingly, some of the boats participating in the regattas were creations of one of Robinson’s other business: boat building. Considering the lack of easily passable roads in the area, boats were the heavily favoured means of transportation.

Naramata was still very young then, and tent houses were common while families were waiting for their permanent homes to be constructed. Still, it was evolving along the lines John More Robinson had envisioned: Naramata as a community that nurtured culture and the arts; that would develop the fine agricultural land; and ensure Robinson’s prosperity as well.

At the beginning, shipping was critical, serving to carry the ever-increasing fruit harvests the South Okanagan produced. Sternwheelers plied Lake Okanagan from Penticton all the way to Okanagan Landing. The first sternwheeler to come to Naramata was the SS Aberdeen which had entered service in 1893. It was followed by the SS Okanagan in 1906, which ran until 1934. It was joined by the even larger and more luxurious SS Sicamous in 1914. Service to Naramata was three times a week. Today, the only remnants of that fleet are the SS Sicamous, permanently beached on the west end of Lakeshore drive in Penticton, along with the tug Naramata that once pulled barges, and broke lake ice with her steel hull in winter.

By 1915, World War I had started and many young men had enlisted to help in the war. In Naramata, the single room school house had been replaced by a two-room school house with a basement to meet the growing needs of the community. That year was also the year the Kettle Valley Railway was completed and the first passenger train arrived in Penticton, the rail line having been under construction during the previous years. The Kettle Valley Railway’s track went east out of Penticton and then north towards Naramata, climbing gently until it passed above the community.

to allow visitors a good look at the spectacular view.

(Click for a larger photo.)

The Kettle Valley Railway

1915 also proved to be the year when the Kettle Valley Railway (KVR) was finally completed and the first passenger train arrived in Penticton. The KVR’s track went east out of Penticton and then north towards Naramata, climbing gently until it passed above the community.

to a visiting CPR Executive, circa 1930. (Click for a larger photo.)

Although the trains would only stop on the Arawana siding if flagged by the Section Man, who resided in the house with the Arawana sign, it still meant a “fast” connection to the outside world for the community; an important psychological connection. For many years the Kettle Valley Railway served the

Okanagan faithfully. Sadly, those buildings were torn down in the 1970’s after the Kettle Valley Railway stopped running, but the general area is still visible today when walking or cycling the KVR Trail slightly north of Arawana Road.

The arrival of the Kettle Valley Railway brought profound changes to Naramata. Where once anything being brought to the area first arrived at Okanagan Landing, and was then delivered by ship or barge, the railway allowed things to be delivered much closer and faster. It also allowed travel to other points inland and to the coast. More importantly, it made it easier for settlers to come to Naramata, thus helping to grow the community.

to the Naramata Bench orchards.

(Click for a larger photo.)

In the arid climate of the South Okanagan, the founding and development of Naramata would have been completely unsustainable without creating an irrigation system to water the ever-increasing number of orchards and farms. The system was built concurrently with the founding of Naramata, and once more, John Moore Robinson was directly involved, creating yet another company, the Naramata Irrigation Company, to handle the construction and receive payments from the orchardists for the water that irrigated their growing trees.

The sheer amount of back-breaking labour that was necessary to build the system cannot be underestimated. Wood being much less expensive than pipe in those days, most of the irrigation system was built with it. Water from the uplands in the hills above Naramata, and from as far away as a lake east of Penticton was partially diverted and funnelled downhill to supply each of the orchards. The water travelled along gullies, and through wood flumes until it arrived at its destination

By 1913, the Naramata Irrigation Company was granted a license by the provincial government to place a dam at a landlocked lake that benefited from snow melt each spring. That first dam in the area would be one of a number, all serving the irrigation needs of the community.

The irrigation network was very extensive and required constant maintenance, with the peak amount of maintenance occurring in the spring to repair any damage that had occurred over the winter months. The extent of the flumes following the contours of the hills above Naramata can be seen in the photograph below. One flume is clearly visible running along the rail bed of the Kettle Valley Railway, while others can be seen in the distance, cutting across the hills above the rail track.

The photo at left shows an area south of Naramata called Three Mile, which is now part of the city of Penticton. The orchards are clearly defined and the ditches that brought water to the trees can be detected as lines running down the orchard in the middle of the photo. Water would arrive at the top of the gently sloping orchard, and a sluice gate would be open in the flume to divert some of the water to the orchard, generally using yet another flume. When the watering was complete, the sluice gate would be closed and the water would continue on its downward course.

In 1917 the community took advantage of a provincial government offer to provide loans for the creation of user-run community Water Boards. The Naramata Irrigation Company continued until 1921 when it was replaced by the Naramata Irrigation District. Today, the Naramata Irrigation District still remains in existence, as part of the Regional District of the Okanagan-Similkameen (RDOS), which looks after Naramata as well as other unincorporated communities in the region.

The Advent of the Elk

The history of Naramata is replete with anecdotes, most dating back to the early years of the community. One of these explains how elks came to this part of the Okanagan Valley, where they were by no means indigenous.

It seems that in the 1930s the provincial government decided that an elk herd should be established in the Kettle Valley, in the general area of Rock Creek, around eighty kilometres as the crow flies to the south east of Naramata. Some thirty elks were soon gathered in Alberta, where they were abundant, loaded into two railway cattle cars and sent out West. Upon their arrival at Okanagan Landing (now Vernon), the rail cars were loaded onto a barge for transfer to Penticton. The elk-filled cattle cars were then loaded onto the Kettle Valley Railway, destined for Rock Creek.

For some reason, the elk were unloaded near the Adra tunnel, above Naramata, and corralled, possibly to give the animals a chance to stretch their legs and feed. But, elk being elk, they promptly walked through the corral’s fence as though it wasn’t there and headed for freedom in the hills above the village

When the next spring came to the orchards of Naramata, so did the elk. Their munching on the new buds caused such a great deal of damage that an elk hunt was organized by the orchardists. The hunt, however, did little to deter them. Further, when Lake Okanagan froze over during a particularly cold winter a few years later, some elk made their way across the lake and established another herd above Summerland. Today, a large elk herd, about 60 strong, still ranges between Okanagan Mountain and Naramata, along with several other, smaller herds. And to this day, many residents of Naramata will have a story or two about herds of elk breezing through eight-foot tall orchard fences as if they weren’t there, all for a leisurely nibble of those tasty Okanagan fruit trees.

This was the first automobile in Naramata. (Click for a larger photo.)

Carroll Aikins: An Innovative Spirit

Carroll Aikins was born in 1888, in Stanstead, Quebec, to a well-to-do business family that had many members in politics and high office. They moved to Winnipeg, Manitoba when he was just a few weeks old. At the turn of the century, Aikins went with his mother to study and travel in Europe. His experience fostered in him a profound interest in the arts, particularly in the theatre, to which he would devote the rest of his life, becoming a well-known playwright in his own right.

Aikins’ move to Naramata in 1908 was motivated by health reasons. Aikins’ father purchased 100 acres of land in Naramata for his son, hoping the region’s dry climate would prevent tuberculosis, which it was suspected he was developing. Aikins’ property was to be orchards, to provide him with an income. There he built one of the most notable houses in Naramata, as it was made of stone, which was very uncommon in the area. He named it Reka Dom, meaning “house by the water” in Russian. The community referred to it as “Rekadom Ranch”. The house still stands today, albeit under different ownership, and it can be seen from Old Main Road, between the roadway and the lake and behind a stone wall.

In 1911, Carroll Aikins brought the first automobile to Naramata. It arrived via the SS Okanagan and was delivered on the pier. The car was an E-M-F 30 Touring Car, which were built in Detroit, Michigan and Walkerville, Ontario.

Aikins married Katherine Foster, daughter of the American Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary in Ottawa (the equivalent nowadays of Ambassador), in 1912. Seven years later, Aikins was not only busy supervising work in his orchards, but also busy producing a play to help the war effort by having the proceeds go to the Red Cross. This first Carroll Aikins play produced in Naramata was probably put on at the “Opera House”, on the upper floor of John Moore Robinson’s Naramata Supply Company. But Carroll Aikins had a plan: he wanted to build his own small theatre above the packing house at Reka Dom, and make it a place to educate and train Canadian actors.

Finally, by 1920 Aikins’ vision had become reality. The theatre was officially opened on November 3rd, 1920 by Prime Minister Arthur Meighen, in Naramata. Aikins was ready to put on productions and take in students of the craft. This was not just any theatre: it was state-of-the-art. A generator which normally provided power for the packing house could instead provide power to light the stage of the theatre. This development was duly noted in the Penticton Herald’s edition on May 26, 1920:

“Mr. Carroll Aikins, of Naramata, works in a quiet way. He has financed and built on his property, one of the coziest, most modern, and up-to-the-minute theatres it is conceivable to devise, and all without the usual blare of trumpet and newspaper advertising that accommodates enterprises of much less importance than that in which Mr. Aikins is engaged. He built the theatre primarily for the education and training of Canadian actors and the Naramata building will be, or is, the home of the Canadian Players. It is the intention of Mr. Aikins to offer the public the higher class productions of the legitimate stage and the residents of the Southern Okanagan will be fortunate in this respect.”

Sadly, the theatre was closed only two years later, as Carroll Aikins ran into financial difficulties due to a severe downturn in the fruit market. Today, Naramatians still remember Aikins, and a street is named in his honour: Aikins Loop, home to several excellent wineries.

The Great Depression

Just like everywhere else, the Great Depression hit the Okanagan hard and Naramata was no exception; the markets for the fruit grown in the Okanagan all but disappeared, and unemployment was rampant. In Naramata, waterfront lots were selling for a mere $10, with few takers.

At the height of the depression, nearly one hundred thousand men crisscrossed the country, desperately searching for work. By the early 1930s, under the government of Prime Minister R.B. Bennett, Relief Camps for unemployed single men were created at both the provincial and federal levels. These camps, run by the military in the case of the federal ones, and with military discipline for those under provincial jurisdiction, were an attempt to keep unemployed workers off the streets of the cities while providing them with meaningful work building roads, along with other federal and provincial infrastructure. Regrettably, in the eyes of the workers, many of the relief camps soon turned into something more closely resembling prison work camps. Paid some 20 cents a day, many men found themselves living in appalling conditions, stacked like cordwood in windowless bunkhouses, labouring six and half days a week in isolated regions.

Indeed, a Relief Camp was located in Naramata, at what came to be called “Camp Hill”, just above the village, in the area where the Naramata Fire Hall is now located. Fortunately, this camp was one of the better ones: the men housed there were generally well-received in the impoverished community.

World War II

When Canada declared war on Germany, seven days after Great Britain, the Great Depression started to fade as the federal government finally borrowed and spent the money it had until then refused to borrow and spend to help the unemployed. Canada fully entered the war in 1942, by which time Germany occupied most of Western Europe and Great Britain was in dire straits. Like their peers across the country, Naramatian men of fighting age courageously volunteered for duty. Seven young men never came back, and their names are inscribed in the cenotaph at Manitou Park.

During that time, the Naramata Hotel was converted to a small boarding school, and some children that had been evacuated from Great Britain spent time there. It was also during that period that nearby Penticton built its airport (an aerial view of which graced the back of the Canadian $10 bill until a few years back), with its preliminary development completed in 1941 so it could act as an emergency landing strip for military traffic during the war.

The 1950 Okanagan Mountain Air Crash

December 22nd, 1950 saw Naramatians save the lives of the passengers of a plane involved in a tragic accident. Canadian Pacific Airways Flight 4 crashed on Okanagan Mountain just after noon due to a signalling light malfunction. The light normally triggered by Penticton Airport failed to activate, resulting in the DC-3 striking the upper slopes of Okanagan Mountain on its approach to the airport. (Read the full story here.)

While the pilot and co-pilot succumbed to the injuries they sustained in the crash, the 16 passengers and crew survived in the cold for over 30 hours, huddled in the shattered fuselage. In particularly brutal weather, rescue parties consisting of Naramata residents struggled to get to the site. On foot, ill-equipped and in the depths of winter, they managed to get to the crash site through three feet of snow, and two days later successfully led the passengers down the mountain to safety at Paradise Ranch, at the north end of Naramata.

Orchards and Vineyards

From the start, Naramata was planted with orchards, as fruit-growing was – and remains – a vital industry for the entire Okanagan Valley. In among the fruit trees, table grapes were also grown. Wine grapes, however, were first grown at the Oblate Mission in Kelowna in 1859 by Father Charles Pandosy, a French Catholic priest, and were intended solely for the production of sacramental wine. Quite some time later, in 1932, the first winery in the Okanagan, Calona Wines, was founded.

By the beginning of 1970s some growers, most notably the Osoyoos First Nation, started experimenting by planting Vitis vinifera varieties such as Riesling, Scheurebe, and Ehrenfelser. The mid-1970s saw the addition of further cold-tolerant varieties, such as Pinot Gris, Pinot Blanc and Gewürtztraminer.

However, the bulk of plantings at the time were of Vitis labrusca, a grape vine native to North America, and of hybrid grapes (crossings of Vitis species), both of which are commonly held to be inferior in taste to the European Vitis vinifera, from which the majority of wine is made. It wasn’t until the arrival of the FTA (Free Trade Agreement) with the United States in the late 1980s, which brought an increased presence of west coast American wines, that the British Columbia government was prompted to provide incentives for growers to pull out their Vitis labrusca vines and replace them with Vitis vinifera to increase quality wine production in the province.

Today, just about every type of wine can be found in the Okanagan, and many are represented on the Naramata Bench, a region that encompasses the benchlands that run from the north-east end of Penticton all the way to Okanagan Mountain Park.

Many orchards remain in Naramata, cheek by jowl with the vineyards. Naramata produces apples, pears, peaches, plums, apricots, and cherries. Nowadays, the cherry orchards can give rise to a surprising sight after a rain shower in early July: helicopters hovering mere feet above the trees, using their blade downwash to blow the rain water off the trees to prevent cherries from splitting.

One can’t help but wonder what the early pioneers of the village would have thought of that…

Sources:

Some black & white photos can be found at oldphotos.ca, the official website of the Okanagan Archive Trust Society, and are courtesy of Brian Wilson, Archivist.

Information for this article came from numerous sources, these are the primary:

- The Okanagan Archive Trust Society, conversations with Brian Wilson, Archivist.

- Smile of Manitou, Don Salting, Edited by Brian Wilson, published by Naramata Heritage Society, 1982, 100 pages.

- Penticton Pioneers, R. N. Atkinson, published by the Penticton Branch of the Okanagan Historical Society, 1967, 220 pages.

- Carroll Aikins and the Home Theatre, James Hoffman, published by Theatre Research in Canada, Spring 1986.

- Wikipedia:

- Okanagan Historical Society Reports – A visual record of the Society’s Annual Report from its first issue in 1926 – UBC Library Digital Collections.

© 2014-2024 Naramata Projects Ltd. dba Forgotten Hill Bed & Breakfast. All rights reserved.